(His recollections of organizing the AO Museum Collection in 1983)

The photos (by Dick Whitney) on this page are of John

Young in the

AO Museum, and were taken in August of 1999. This was

prior to the DOD

project, and are among the many photos that I archived of

the AO Museum

as it was in the Main Plant Facility. John has been a long

time friend

since we both worked together at AO in the late 1970s.

Thanks to Zeiss, the Museum reopened in 2013 and is

presently located at 12 Crane St, Southbridge.

http://www.opticalheritiagemuseum.com

John passed away in June of 2017, and will be greatly

missed. Read his recollection of the start of the Museum

which would not exist today without his perseverance to

establish it back in 1983.

John Young wrote the following about the Museum:

The

roots of American Optical go back to 1833, as most

people in the area are

now aware.This

means that American

Optical has not only been in operation for over 150

years, but has also

had 150 years to accumulate all kinds of stuff.Everytime

company management would move the treasurer’s office or

the gold assaying

area, or just plain out grew the current space, the old

‘walk-in safe’

in that area was just abandoned and sat there through

time filled with

stuff.That stuff

eventually became

old and valuable.

The

museum got its start when a group of us in Marketing

began to talk about

how to take advantage of the 150th birthday of American

Optical.There

were, of course, several projects that were completed

which would advertise

this to our customers but something did happen that

started us down another

road.Someone said

that they had

heard that there was a vast storehouse of old frames

that we might want

to give away to our customers during the celebration.This

celebration had just started into the planning stage for

the Optical Laboratories

Association Convention, which as I recall was about

seven or eight months

away.That comment

struck several

of us the wrong way and didn’t get very far before

someone suggested that

a steering committee be formed to look at all the

possibilities for our

customers, our employees and our town.

With

a little digging and some questions to the folks who had

been around for

a while in the company, it became apparent that there

was, indeed, a collection

of antique eyewear scattered around the buildings,

who-knows-where!At

the

first steering committee meeting, there had been

suggestions of a parade

and an open house.I

had suggested

the idea of using the antique materials in a display of

some sort or a

mini-museum.In

the Army, you’re

taught never to volunteer and I suppose that goes for

ideas as well, although

I do seem to recall others with a similar concept at

that steering committee

meeting.Anyway, I

was never in

the Army and thus, I had the project assigned to me to

chair its creation.Whoa!Where

to

begin?

That

is actually when the real fun began.I

remember a group of novice volunteers charging excitedly

around the main

plant after hours with flashlights looking for what we

had heard was the

true “piece-de-resistance.”This

was reported to be one or more frames that had been

individually cast and

filled with precious jewels; we felt like we might have

been in search

of King Solomon’s treasures.The

members of that volunteer team were Marge Breen, Dave

Butler, Priscilla

Butler, Cris Waldron, Brad Noble, Addi Perry, John

Mikoljaczak, Sandy Neiduski,

Connie Borey, Sandy Furioso, Milt Freeman and later on

even Ruth Wells

herself joined in the project of restoration of frames

we had uncovered.

In

the dark, we felt like plunderers of the past as we

opened the main plant

safe in the treasurer’s office, a move which would

later, in day light

hours, be lightly frowned upon by management.Thankfully,

we had Dave Butler with us and he was the Director of

Plant Security at

the time.He may

have taken a bit

more ‘heat’ for the endeavor but, if he did, he never

admitted it to us.The

five

jeweled frames that had been reportedly cast for the

Madame Schaparielli

signature design series were elusive.Then

while looking in a small box of what appeared to be a

wrapped cleaning

rag, we found something that would give the whole museum

venture life and

push us forward in our endeavor.

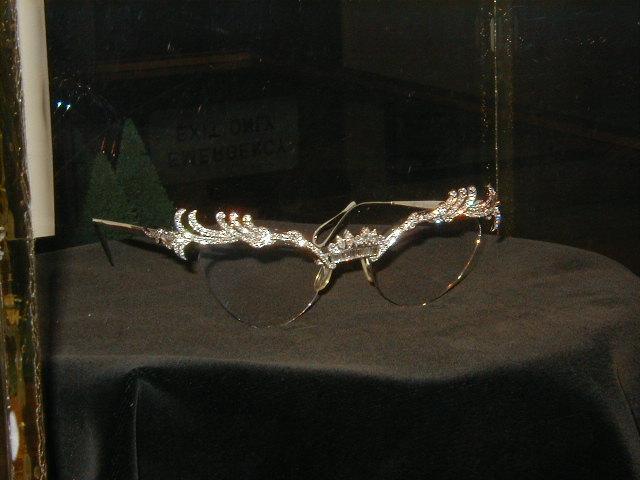

As

we unwrapped the cloth in that dark, dank safe, we could

begin to see the

sparkling of a brilliant frame of iridium platinum

containing what we would

discover was 201 diamonds with a weight of 7.5 carats.This

frame became the true leader of what would follow and

what followed was

a committed group of volunteers, working late at night

and weekends after

everyone else had gone home, cleaning and polishing the

old frames and

lenses we had found in our many expeditions through the

main plant.During

these expeditions, we found a total of 4,3000 antique

frames, 2,500 glass

negatives of early Wells’ family photos, AO and

Southbridge people (later

donated to the Southbridge Historical Society); what we

believed to be

the third AO LensometerÒ commercially manufactured

designed by Tillyer,

the Todd/AO reel of the movie Oklahoma, and other

numerous items.All

of

it was exciting, like being a pirate of old, except this

was legal and

for a good cause.

The

Schaparielli frames were originally produced to

introduce the first ‘signature’

series; the first time a ‘signature design’ series had

ever been offered

by anyone for any product.The five

originals were hand cast, then mounted with jewels.These

were then offered to AO’s better practitioner customers

to display in their

windows for a short time.Of

the

five frames, the only frame that was duplicated was the

diamond inlaid

frame and it is the only surviving frame of that

original collection of

five.It had been

reproduced at an

unknown price for someone in England.

One

night while foraging in one of the old vaults, we began

to pull out dusty

packages wrapped in brown butcher paper and tied with

twine.As

we opened these ancient time capsules, it began to

appear that they were

sarcophagus for spectacles; all new! Around

1904 to 1908, American Optical found themselves in two

situations; they

were becoming a global operation, and they were being

copied due to their

success.George

Wells hired a number

of attorneys to watch over the possibility of patent

infringement which

could injure the growth of the company.What

better way than to buy any new frame on the market and

compare it to the

product that the company was producing.So

they did.

What

we found was probably the foremost collection in the

world of what was

called “Pince nez” which, according to Ruth Wells, was

simply French for

‘Pinch Nose’ and pinch they did, we all tried them.the

amazing part of this was that most had no lenses because

they were purchased

before they had been made up as complete spectacles.Some

even had the original tags on them.But

all of them were carefully mounted on dark blue padded,

velveteen, frame

boards.I still remember Ruth Wells

taking on the task of removing each frame, carefully

cleaning each of these,

and each of the many velveteen mounting boards that had

been found.

Ruth Wells was always there taking part in her own history, unselfishly working on those dusty old frames, which were part of 114 years of her family’s past.She also gave us the many Wells family photos seen in the current exhibit. While she is no longer with us, we are very fortunate to have the taped interview she and others consented to give to us for our audio history as remembered by those who were there.She is dearly missed by many but she certainly left a legacy of grace for us all to remember.

Meantime,

the material was going to need a place to be displayed

and the room in

the main plant where it now resides was chosen.The

room had been used to display current AO products up to

that point and

what better place to situate the museum; a museum which

had by this time

taken on a life of its own, dragging all of us along

with it.I’m

told by my wife, Patti, that she is officially the first

‘museum widow’

and I’m equally sure that other volunteers were in the

same situation.What

was

most amazing was that there was never even a whisper of

complaint about

the time everyone was putting into this task.We

worked a total of nine months this way.I

can remember carrying a dictating machine everywhere I

traveled.I

was mentally moving from one piece to another along the

cases in the yet

unveiled museum listing the description.Sandy

Neiduski then typed up a total of 16 hours of that

dictation to complete

the small information tag that is found with each item

in the museum.There

was

a very real deadline to meet.That

future opening day couldn’t be changed because a very

large contingent

of Shriners had committed to that date for the gala

parade planned to come

through town, the appropriate State Representatives were

all coming, as

well as the families of the entire workforce; not to

mention the owners

of the corporation.

All

of the work in the museum was completed by the inside

talent that American

Optical had available.These

were

the true craftsmen, some capable of building the

beautiful solid oak cabinetry

seen there.Others

from the AO machine

shop were equally skilled and completely restored the

old flat belt driven

polishing machine which operates in the corner of the

exhibit area.How

many kids would never ever see such a device were it not

for the skilled

hands of those machinists.these

men were as proud of the museum as we were.Even

the American Optical Patent Attorney, Basil Prince, got

involved.In

the creation of the old pine jewelers caged bench, we

needed some authentic

clock

works.Basil, an

antique clock enthusiast,

came to the rescue with a bunch of clocks just perfect

for our needs.So

many reach out to take part and give a little of

themselves during this

effort, that it would be hard to list them all.

Not

all decisions were necessarily good ones, however.A

retired pair of doctors from Springfield had heard about

the efforts at

AO and donated their entire offices to us.Southbridge

Trucking was kind enough to give us a break on cost and

sent out their

crew and tractor trailer to pick up the goods.In

the meantime, I had gotten a call from the Worcester

Science Museum.They

had

one of the doors to a safe from the first building in

the complex at

American Optical to assay and store the gold for the

production of frames.It

had

apparently been replaced or possibly torn out in an

early renovation

when the wooden buildings were covered with brick and

mortar at the turn

of the century or perhaps when the frame operation moved

to the new frame

plant during World War II.

In

any event, here was this huge door and they wanted me to

accept it as their

donation to our little venture.I

did.It was an

unfortunate decision

as the same crew who was moving the material from

Springfield were now

going to have to move this thing as well.It

was indeed a beautiful door, but I had no idea what to

do with it.It

seemed a shame to lose such a piece of memorabilia from

the past, even

though it weighed in at over a ton.Something

like being given an elephant, I suppose.Anyway,

it was moved into storage in the basement of the main

plant where it sat

for years.I’m

sure that there

were many who were looking for good storage space who

cursed me and my

door.

The

material that had been donated by the good doctors was

laboriously cleaned

and repainted in the dank basement of the main plant by

that same relentless

volunteer crew who prepared everything else for that

opening day.It

was then moved into the room opposite the museum exhibit

area.It

remained there for some time as part of the overall

exhibit.Other

items were also donated from quite a wide variety of

people coming from

a number of areas of the country.

Keeping

these ancient pieces in good shape was important and no

one in the group

had ever had curatorial experience.In

several contacts I had made with Crawford Lincoln,

Director of Old Sturbridge

Village, I had found him and his staff always willing to

help.They

advised us of a seminar on this subject coming up right

at the Village.So

off we went to learn what we could about the care of our

growing collection.As

time

went by, I found myself going back to OSV many times to

discuss issues

with their many experts who were always willing to lend

a hand to these

newcomers.

Once

the museum began to take shape, there was a need to get

it appraised for

the insurance company that insured everything else in

the AO complex.This

was

going to take a specialist in the field and I had been

told of such

an individual in New Orleans.He

was an ophthalmologist who collected spectacles and was

also, coincidentally,

the Chief Curator the American Academy of Ophthalmology

Foundation Museum

in San Francisco.As it turned out,

Dr. J. William Rosenthal became a true friend of the

museum and mine as

well.He has

donated a number of

articles to the collection.He and

I also decided that it might be fun to start a group who

had similar interests.the

outcome

was the Optical Heritage Society which meets once a year

to spend

a few days in different areas of the country giving, and

listening to seminars

on anything to do with antique eye apparatus and

spectacles, of course,

were included at the top of the list.It

has grown appreciably over the years since the first

meeting at the American

Optical Museum.Bill

was one of

the first Directors of the AO Museum and is still

interested today in what

becomes of the collection.There

may be better collections in the world but it’s doubtful

that there is

a larger one.

As

the date approached for the opening, things got fairly

hectic.The

final items went in place the evening before the

official opening.The

following

morning before the festivities began, Gene Lewis, then

President

of American Optical, was just coming through the door,

coming in directly

from the airport.He

had just arrived

from a two week business trip to China and the first

thing he wanted to

see was the museum, it was finished.Whew!,

that was close!Gene

had always been

a staunch supporter of the museum from those first

estimates I had submitted,

to when he found out how much it was really

going to cost the company.

The

museum opened on weekends for a while manned by the same

group of volunteers.There

were

even photos and brochures at the Sturbridge Tourist

Center telling

people to come on down to see the museum.This

faded in time but Marge Breen gets the award for

tenacity.She,

situated one floor above the museum, was who everyone

called to see the

exhibit after it had been closed.

The

venture was a learning experience for all of us.I

think now that some of the things learned were actually

the experiences

enjoyed as all of it went together.The

team of people who gave freely of their time became

close friends and had

our own little celebration when it was finally done.Then

there are the people who donated family treasures to the

museum and those

who offered their skills to see the task successfully

completed.Even

those who cheered the project and rooted us on helped

the group immeasurably.For

me

it was the people I got to share it with, the education

in history about

spectacles and a spectacle town’s people that I’ll never

forget.